Excerpt from CHILD OF A RAINLESS YEAR by Jane Lindskold.

To be published by Tor Books in May 2005. Copyright © 2005 by Jane Lindskold. All rights reserved. No part of this text may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission of the Publisher. Exceptions are made for downloading this file to a computer for personal use.

(These exerpts are based on uncorrected proofs and may slightly differ from the published version of the novel.)

“Just what colors our attitude toward color? Too much and we risk not being taken seriously; too little and we fear being dull.”

—Patricia Lynne Duffy, Blue Cats and Chartreuse Kittens

Coloring Inside the Lines

Color is the great magic.

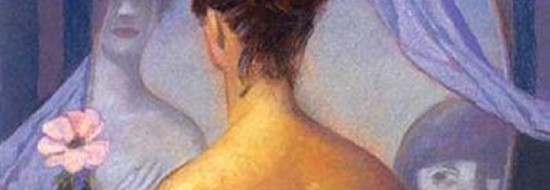

I learned that one day as I watched my mother preparing for the most recent of her lovers. She, intent on the mirror over her elegant, gilded vanity, did not see me as I watched her from a mirror set in the border of a picture frame, two reverses making the image right again.

I was some years older than I had been in that rainless year when I had been born — five, maybe six years old. Mother had been very angry with me earlier that day. Then she had forgotten me, as she often did when she was so intensely displeased that even the “my” of her wrath could not ease her pain. Easier to forget.

So, forgotten, I went where I was usually forbidden to go, into Mother’s private suite, sneaking in while she was in her bath, hiding in the corner near a full-length framed picture of her painted to commemorate some past triumph. I turned my back on the room, viewing the chamber only through the mirror set into the picture’s frame.

I hid well, for — although, now, from the distance of these many years, I can see that I wanted to be found, to have her make me real again even if through the fierce force of her anger — I also feared that anger. Better to be tentatively real in hope, to breathe in the mingled scents of her room, of the perfumes she wore, of the lavender in which the bed linens were packed, of the cedar that lined her closets and clothes chests.

When Mother emerged from the bath she wore a scarlet Japanese kimono trimmed in gold, embroidered with patterns of tigers and phoenixes. Her glossy hair was wrapped in a towel that was a precisely matching shade of scarlet.

Her first task upon entering the room was to bend at the waist and rub the excess water from her shining black hair. She slowly combed the tangles from her hair, never tugging lest one of the long, dark tresses break.

Combed, that dark curtain hung past her waist, and because I knew she was proud of that shining dark fall, I felt proud of it as well. I watched with my breath held as she pulled her hair back and inserted it into a silver clasp, never breaking a single strand.

Hair combed and clipped, Mother seated herself at her vanity and viewed herself in the mirror. She dropped her robe from her shoulders and sat naked to the waist, the breasts that had never nursed me almost as firm and round as those of a girl.

She leaned forward, her gaze intent on her face, on the skin still slightly dewed from her bath. Her gaze was intent, studying those high-cheekboned features critically, looking for any lines, any trace of the sagging that comes with age. There were some, for she was past the first bloom of youth then, and this dry climate is not kind, even to those who live sheltered from the burning sun.

Yet, even though this was a critical review, I could sense Mother’s pleasure in what she saw. It was her face, after all, and like so many who look at themselves too often in mirrors, she thought that this reverse image, seen rigidly straight on as we are so rarely seen by others, was her truest self.

I was the one who was shocked. This was the first time that I can remember seeing my mother with her features unadorned by cosmetics. This was a different face entirely from the one I knew. Her brows were as pale as my own, her skin — if possible — more sallow. Even her eyes, usually deep blue where mine were hazed blue-grey, were not the eyes I knew, their color pale and less vibrant.

I shrank back into my corner, watching in the least corner of the mirror as my mother worked the transforming magic of color upon her face, watched as tints from fat, round pots gave her sallow skin smoothness and warmth, watched as her skillful fingers defined some features, diminished others.

Eyebrows were sketched in, dark as the fall of her hair, their tilt mocking and ironic. Tiny brushes pulled from slender vials made her eyelashes longer, painted in subtle lines that made her gaze more compelling. Powders dusted color onto eyelids and along the rise of cheekbones.

I watched, mesmerized as Mother transformed herself from a pale ghost into the beauty who still commanded legions of admirers. Fear throbbed tight and hard within my chest. No longer did I want to be discovered, for I knew I had stumbled on a mystery greater and more terrible than that of Bluebeard’s murdered wives. I had seen the secret magic of color, and how color made lies truth and truth lies.

Even at that young age, I knew I could not be forgiven my discovery.

But perhaps what she believed is not so impossible. Overall, my mother was not a simple soul, yet in one crucial way she was. Beneath her intelligence and an education that was far beyond what most women of her day received, Mother was a horribly egotistical woman to whom nothing was real unless it happened directly to her.

So, perhaps, in a way, my mother spoke the simple truth and there was no rain in the year I was born. Perhaps none fell near her, the scattered clouds that are what this desert land knows best, shying from the heat of her self-conceit as they shy from the thermal updrafts that well from the baked black lava outcroppings.

She was not a cold woman, my mother. Not in the least. Indeed, the welter of her egotism made her very hot. She felt any slight passionately — any slight to herself, that is. Slights to another, even to those she claimed to love she seemed indifferent to, yet she was not indifferent, for to be indifferent you must notice.

Mother noticed only rarely, and then in such a personal fashion that the one so noticed would cringe, wishing to have that egotism turned elsewhere, anywhere else, rather than suffer the wails mourning the wrong done to “my” — “my child,” “my efforts,” “my pain,” “my sacrifice,” “my…” Truly, for her, nothing existed outside of that curtaining veil of self.

To some men, Mother was irresistible. If they thought at all why this was so they would speak of her charm, her gaiety, her beauty, her intense pleasure in life. If they were honest and considered beyond this easy answer, they admitted to themselves that they desired to be the one who would succeed in getting beyond that tremendous ego, but of course no man ever succeeded — not even my father, who got beneath so much else.

Other types of men — those who themselves were egotistical in their obsession with self, those who were gifted with empathy so rare in men, those with purpose so great that it carried them outside of themselves — all of these kept from Mother as the rain did during that year she carried me, the year I was born.

Even my father kept from her in time, so that by the day of my birth ours was a household of women: silent women and a host of mirrors. Mirrors hung in picture frames and in stands. They rested within long-handled holders on the tops of polished dressers. They awaited the unwary in unlikely places: hung on the backs of doors usually kept open, beneath the accumulated heap of scarfs and hats on the coat-tree by the door, in the kitchen over the stove, even as tiny rounds set into the fabric of elaborate skirts and shawls.

I knew myself through those mirrors as most children know themselves through the stories others tell them. No one in that strange household of silent women was going to waste word or breath on me — child of a passing fancy, child of a rainless year.

I saw myself in those many mirrors: round eyes the color of a heat-hazed sky, fair skin blushed with ash, thick straight hair pale as winter sunlight. I had none of my mother’s beauty, none of her vibrancy. For a long time, the only thing that connected me to her was the “my” that prefaced her every mention of me, for I had no name to Mother that did not relate to her. I was her “daughter,” “darling,” “treasure.” Later, when I grew older and gave her reason to be displeased, I was her “nuisance,” “burden,” “trial.”

When she was truly displeased with me, Mother denied me even that connecting “my.” Then I felt stripped of identity, bereft of an increasingly tenuous hold on reality. Sometimes I found myself wondering when Mother would discard me as I had seen so many past treasures — gowns, jewels, lovers — be discarded when they failed to please her.

So little respect for myself did I have that this prospect did not trouble me in the least. That I would eventually be discarded seemed right, for in that house we were all her satellites and she the center of gravity about which we revolved.

Initially, Mother set herself to be my teacher, but this proved — as even I could have warned her — to be a catastrophic venture. For one thing, I proved to be left-handed, and although Mother tried to break me of this “clumsiness,” she failed. I was a lefty, then and forever after.

The failure to learn from Mother’s teaching was assigned to me, never to her. Even I accepted this verdict as true, never questioning that Mother’s erratic methods might not be suited for a young girl hardly able to see over the edge of the polished mahogany desk where we sat facing each other for some hours each morning.

Next, Mother assigned one of the silent women to be my teacher. This attempt, too, was a failure, for Mother frequently hovered in the vicinity of our makeshift schoolroom. She stayed just out of sight around the corners of doorways, her image relayed flickering and fragmented in the mirrors, so both I and my hapless tutor knew she was there.

By this time I had learned that the silent women did indeed speak — sometimes volubly — but never when Mother could hear them, nor when they knew I was near. Presumably they, like my mother, assumed I was nothing more than an extension of her will. I could have told them they were wrong, but at this time I had no idea that anyone would care to know.

Among themselves, the silent women spoke a language I didn’t know, but that sounded familiar. When they did speak in my presence, they spoke English, but without any trace of an accent, certainly without the accent of northern New Mexico.

Intimidated into more usual muteness by my mother’s nearness yet forced by duty to speak, the silent woman, my tutor, tried to teach in whispers and by pointing to the pictures on pages. Her voice made no more sound than two leaves brushing together, thus each letter of the alphabet came to my ears as the creak of the floorboards where my mother paced, as the rustle of her skirts.

Needless to say, I learned little of the relationship between the letters of the alphabet and the sounds they represented. I did learn something of their shape and how to draw them with elegant accuracy in the blue-lined copybook.

After the failure of the silent woman came a string of private tutors, each a bright bead on the string of my memory. None lasted more than a few weeks before Mother’s impossibly high expectations drove them off. One, a grey-haired woman with a carriage so stiff and upright that I imagined her spine to be made of a metal rod, like those in the dress stand on which Mother aired some of her finer gowns, lasted for nearly a month. She was the first not to begin my lessons by trying to make me write with my right hand. For that alone I would have loved her.

The grey-haired woman raised her voice to Mother before taking her final leave, the shrill harshness of her anger carrying even through the solid wooden door that separated the library from my mother’s parlor. There I waited, watching myself in the mirror that backed the parlor door, knowing myself disgraced once again. I could not make out a single word, but this was the first time I heard anybody raise their voice to Mother and so this tutor’s departure made a great impression on me.

I saw this former tutor once or twice after that, striding past on the sidewalk outside of our house. She looked up at the front parlor window once. I thought she might even have seen me there, cuddled into the window seat, hidden from view to those inside the room by the thick fall of velvet curtain. She gave no nod, no acknowledgement, and that omission hurt me until I realized that the glazed glass turned back the light. If she had seen anything she had seen her own reflection.

The thin grey woman was my last tutor. After that, Mother was forced to send me out to school. She did not choose the public school that served to educate the heterogeneous mass of the town’s children, but an elect seminary run by a woman who, so rumor said, was an unfrocked nun.

Our Lady’s Seminary for Young Ladies was not a typical school, nor were the students typical students. Even so, it was here that I received my first inkling that my home life might be — to put it mildly — unusual. Here, too, I was first introduced to the ways that I might claim the magic of color for myself.

Many years later, I would find there was a reason for this omission, but when as a girl of seven I began at the seminary I had not the faintest idea.

Although the seminary aspired to grandeur, the relative isolation of our town’s location kept the staff smaller than one might have expected of such an institution, for the headmistress would only hire those who fit her stringent criteria. Then, too, the headmistress may have preferred having this excuse for a smaller staff, since more of the tuition remained in her own pockets.

For whatever reason, drawing and painting were taught by the same woman who taught us poetry and literature, a delicate woman who reminded me of apple blossoms and the tiny, fragile flowers that appear after the rains, growing apparently from nothing.

This teacher’s name was Emily Little. She was a widow with a very young daughter, almost a baby. While her mother gave us our lesson, the baby stayed down in the kitchens with the stereotypically fat and comfortable cook. Sometimes there would be a tapping at the classroom door and Mrs Little would excuse herself and tell us to mind ourselves for a moment, then go hurrying down the corridor, leaving the classroom door open to assure we would behave. We would hear her footsteps tapping down the polished wood of the hallways and know that some mysterious crisis had transformed our teacher — at least temporarily — into a mother.

By the time my mother enrolled me at the seminary, I was already too old for finger paints — if anything so messy would ever have been permitted in this austere and select establishment. Even so, we were young enough that Mrs Little did not move us to strict fine arts all at once. She had the natural wisdom of one who knows children are not little adults. She knew that if we were to love art, we must associate it with play — even as those children who are read rhyming verse long after they “should” have outgrown baby books grow to love music and poetry.

Therefore, Mrs Little did not start us with watercolors or even those bright, garish poster paints so beloved of the classroom. She wanted us to get a feel for drawing without the worry that our medium would soak our paper, yet she wanted us to have something that would allow us to explore our potential. What she gave us was a pad of paper and a box of crayons.

These were not the fat crayons usually given to children in those days, thick, waxy and yielding very little in the way of color unless one pressed so hard that drawing anything other than bold lines was impossible. What Mrs Little gave us were the slim crayons about the diameter of a standard yellow pencil, solid but requiring a more delicate touch if one was to use them without snapping them.

As I mentioned before, I had never seen anything that drew in color, and I think I would have been fascinated by a box containing nothing but those most basic colors found in every color box: red, yellow, blue, green, and black. However, wonderful as these might have been to me, they would have been boring to most of my classmates. Mrs Little knew this, and so for art class each of us was issued a box containing not five, not twelve, not twenty, but twenty-four slim waxy sticks, each wrapped in paper of a shade approximating the crayon’s own color when rubbed with moderate pressure across a sheet of white paper.

The other girls in the class cooed with delight when Mrs Little handed the boxes to one of that week’s classroom monitors, then gave a stack of pristine drawing pads to the other.

“Put your names on the box of crayons,” Mrs Little said, “and on the drawing pads. You will be using the same ones all term, so handle them carefully.

We did this. I saw a few of the girls pull out a crayon and use it to write their names on the note pad, but uncertain how these worked I printed with my ballpoint pen. My erratic stream of tutors had managed this much at least. I knew my letters and numbers, and could read and do basic figures as well as most of my classmates — even if I did not surpass my peers as Mother thought I should.

“Now, today,” Mrs Little continued, “I want you to draw me the story of your summer vacation.”

A hand shot into the air. Hannah Rakes. A nice girl, but bossy, and full of questions.

“All of it, Teacher?”

“Pick something that you particularly liked.”

Another hand. Mary Felicity — always called by both names, never by just one, though she wrote them as two distinct words.

“Teacher, my family went on two trips. Can I draw both of them?”

“You may. You may draw several pictures if you wish.” Mrs Little seemed to anticipate another question coming. “Keep it to, let’s say, five in all.”

All around me, girls were sliding open the tops of the little rectangular boxes. A row away, Hannah already had a crayon in hand and was making red lines on the first sheet of her drawing pad. I stared, fascinated. Then I heard the rustle of skirts and smelled the vanilla scent that always surrounded Mrs Little.

“Mira, why aren’t you drawing?” she asked, her voice soft and friendly.

I fumbled with the box, and something in the clumsiness with which I opened it told Mrs Little of my unfamiliarity.

“Is this your first time playing with crayons?” she said.

There was no incredulity or criticism in her voice, so I answered with easy honesty.

“Yes,” I admitted.

“They’re great,” Mrs Little said, shaking one out and holding it almost like she would a pencil. She stroked a few lines diagonal lines on one corner of the paper.

Sky blue. I still remember each line. There were three of them, each no more than three inches long. Each a wonder and a revelation.

Mrs Little took out a green crayon, then made a few vertical lines at the bottom of the page. Already I could see sky and grass, and my fingers were itching to try for myself. Mrs Little understood my eagerness and slid the green crayon back into the box.

“Have fun,” she said, and patted me lightly on the shoulder, before moving down the aisle to talk to the girl who sat behind me.

I heard Mrs Little say something approving, ask a question, heard the answer, but the sounds seemed very far away, drifting and dreamy, like sounds heard when one is falling asleep — only I was not falling asleep. I felt quivering and alive, desperately and inordinately happy.

Almost as if possessed of their own volition, my fingers slid out the green crayon. I noticed the slightly blunt edge on one side of the tip and immediately understood that the crayons would wear down, lose their sharpness, just as a pencil did. Carefully, as I might have tested my bath water before getting into the tub, I drew a green line on the page, right next to Mrs Little’s.

It was so faint I could hardly see it. I tried another. Too heavy. For what must have been twenty minutes, I drew blade after blade of grass until I had command of how much pressure it took to make the lines I wanted.

Then I discovered that there were other green crayons in the box, both darker and lighter. I mixed these shades in, thinking of the grass I had seen up close when I had laid on my stomach out in the shadowed shelter of our walled back garden, remembering how it was rarely all one color.

I moved on to the sky. Hatch marks had seemed right for the grass, but didn’t for the sky. Glancing around, I saw that Hannah was rubbing her crayon energetically back and forth. I tentatively tried this, experimenting until I had a blue sky creeping down the page to touch the grass.

Blue sky, green grass. Not much of a picture, but it was my very first. Also, given the flat prairie that bordered one edge of our town, it was not terribly unrealistic.

I turned the page and looked at the fresh white sheet with interest and enthusiasm. What would I draw next? The red crayons had been crying out to me ever since I saw Hannah draw what (as I saw when I snooped) proved to be a very boxy house. I didn’t want to draw a house, but I thought that I might try a rose bush. We had lots of them in the back garden, and I liked them immensely — even the gently curving thorns were interesting.

My fingers were touching the red crayon when Mrs Little clapped her hands together in the sign to stop.

“Art period is ending,” she said. “Please put away your crayons, close your drawing pads, and pass them forward to the monitors.”

There were a few groans of disappointment, and one of them may well have been mine. However, I felt far too happy to really make a fuss. Something had come alive in me that past hour, something that remained alive even when I folded shut my drawing pad and closed the almost untouched box of crayons. I held that happiness to me, and carried it with me as we trooped off to find what the cook had concocted for our mid-day meal.

My name was on both my drawing pad and the box of crayons, sufficient promise that we would be doing this again.

Sometimes, as when I stared fascinated at a picture of a dog chasing a ball, I revealed myself — as I had on the day I first saw crayons — as having lived in relative isolation. I think Mrs Little noticed, but I don’t think the other children did. I was already enough a stranger — a new girl among the old girls — that I did not stand out as strange for my manner.

I was not the only new girl, but I was among the quietest. The buzzing little hoard of girls tried to draw me out with varying degrees of success. Hannah, in her friendly, bossy way was my chief interrogator. Through her questions and through what she did and didn’t find odd about my answers, she also became my chief source of information about the world outside of the one I had known.

Hannah liked to ask questions, but even more than listening to my answers she liked to talk. Listening to her chatter about her home, her cat, her dog, her brothers and sisters fascinated me. I had only the vaguest idea of what she was talking about — my mother kept no pets, and I had no siblings. At first, I thought Hannah must live a very exotic life. Then, as I listened to the other girls, I realized the truth.

My life was the strange one, not theirs.

For one, all of the other girls, even those whose parents were divorced, separated, or — in one very interesting case — dead, knew who their fathers were. I was the only one who had no idea who my father was. When Hannah asked me about him, I said he had been gone for as long as I could remember. Hannah decided this meant that he was dead, and being a nice girl also decided that I wouldn’t want to talk about such a sad thing. She told the other girls her version of the truth, and so I was saved from questions.

At least from other’s questions. From the questions that were now suddenly alive in my imagination I had no relief — and I knew better than to ask anything of my mother.

On the whole, I did not mind my lessons, but they did come most to life when color was involved. Even writing on the blackboard was more fun when the chalk was yellow rather than white. When I discovered that chalk came in pink and blue and green as well — these pastel shades as etherial as I imagined fairy wings to be — I lived and breathed in hope that Mrs Little would let me write in color.

She was not slow to see that this was a painless way to motivate and reward me. Before long I learned to write a neat hand and behaved myself to perfection in order to win the privilege of writing announcements on the board.

Another privilege was going to fetch something from the supply closet. There I saw pens and colored pencils stacked on the higher shelves. There were bottles of powdered pigment for paint, and stacks of construction paper. After that, I daydreamed about colored inks, and anticipated the day that we, like the bigger girls, would use paints. Already, I guessed how wet tints would blend and flow as crayons, for all their beauty, would not.

But for all that my school days were alive and livened with color, I never mentioned my art classes at home. I had never forgotten seeing my mother give herself a face. A sense that anything to do with color was forbidden knowledge stilled my tongue.

I suspect that for once Mother’s obsession with “my” and “me” aided me in my deception regarding colored art materials. She found it so difficult to perceive me as anything other than an extension of herself that she forgot to forbid my exposure to these things until it was far too late.

Her inability to comprehend my life apart from her was so complete that once out of sight I was truly and completely out of mind.

Or, maybe, something else was working in my favor, and I am being unfair to my mother. The only thing I can say is that honestly I am still too close to the matter — even now that decades have passed — to honestly judge.

Excerpt from CHILD OF A RAINLESS YEAR by Jane Lindskold.

To be published by Tor Books in May 2005. Copyright © 2005 by Jane Lindskold. All rights reserved. No part of this text may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission of the Publisher. Exceptions are made for downloading this file to a computer for personal use.

Copyright © 2005 by Jane Lindskold. All rights reserved.