Real Lives are Untidy

Childhood

It is something of a truism that writers tend to be solitary people. Someone once did a study showing that an astonishing number of writers are either eldest or only children — the presumption being that a certain degree of personal isolation helps form the creative impulse.

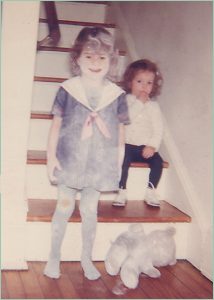

As the eldest of my parents’ four children, I fit this model perfectly, but when applied to me it’s a deceptive statistic. The next child after me, my sister Ann, is less than two years younger. My brother, Graydon, was born on my third birthday. That means I don’t consciously remember a time when there weren’t others around and that contact — as much as the isolation that was a reality until Ann grew old enough to become a real playmate — had its role in shaping my writer’s mind.

I might have been set apart by the responsibilities that are almost unconsciously placed on an eldest child by even the best parents, but I was also very aware of being part of a group. The four of us played together, fought with each other, and, I think, would have defended each other from anyone else in all the universe.

The awareness of being part of a larger entity has had a very real part in shaping what I write about. Byronic loners and mysterious orphans have little attraction for me. Even those characters like Sarah, the protagonist of my Brother to Dragons, Companion to Owls, who appear to be orphaned and alone often end up with families — though those families may be recruited rather than the result of an orderly nuclear family situation.

I also think that this sense for group dynamics is one of the reasons I am drawn to writing about wild canines. There are no lone wolves in my stories — or lone coyotes. Characters like Shahrazad (Changer and Legends Walking) and Blind Seer (Through Wolf’s Eyes) belong to packs and families. They have an awareness of how they fit into that structure. Even as their status shifts over time, the group dynamic is never absent.

My final sibling, Susan, is almost eight years younger than I am, but she, like the others, had her part in making me the writer I am. Not only was Susan a part of my “pack,” she was also someone who wanted to play games of pretend long after they had ceased to hold as much attraction for the other two. Together we wove elaborate frameworks to suit our motley array of plastic figures. Two of these — Steve and Mac — Susan rescued from oblivion for me. They sit on my desk along with the two-headed rubber dragon who is the original Betwixt and Between.

My parents, John and Barbara Lindskold, met in Washington, D.C. D.C. and its environs were where the four of us were all born and where I spent pretty much all of my first eighteen years. The Smithsonian museums were free, as was the National Zoo. Our parents made us comfortable with both. When we grew older they didn’t hesitate to let us adventure into either on our own.

Summers we didn’t tend to go on vacation. Instead we spent holidays at a little cottage on the Chesapeake Bay. The Bay was heaven for me. A neighbor let us play in his wooded acreage where we built lean-tos, foraged for berries, and generally ran wild. We had a small virtually unsinkable rowboat at our disposal, and catching blue crabs became something of an obsession for me. There was a marshy peninsula we dubbed “The Island” to which we could swim or row for picnics.

Summers we didn’t tend to go on vacation. Instead we spent holidays at a little cottage on the Chesapeake Bay. The Bay was heaven for me. A neighbor let us play in his wooded acreage where we built lean-tos, foraged for berries, and generally ran wild. We had a small virtually unsinkable rowboat at our disposal, and catching blue crabs became something of an obsession for me. There was a marshy peninsula we dubbed “The Island” to which we could swim or row for picnics.

Growing up in D.C. had a more subtle influence as well — one that would have an enormous impact on my writing. Politics, complex and cynical, are the lifeblood of that city. My grandfather was governor of Ohio when I was very small. Through him and my mother’s own early career we knew politicians and people who worked “on the Hill” as real human beings, not just awesome figures on television.

Yet, even as I grew familiar with the mechanics of how government worked, I was aware of being disenfranchised. Living in the place where laws were made, yet knowing that my own vote would count for nothing made me less than idealistic about the ultimate goals and purposes of those who rule.

I can no more write about a dark lord of ultimate evil than I can a shining king of perfect virtue. Shades of grey are what fascinate me — those and the realization that the best ruler may make choices that may seem quite wicked, while the worst ruler might feed the poor in order to gain their servile support.

Education

My parents placed a high value on education and went without a good many creature comforts to make certain we all had the best they could provide. Except for a brief stint in public schools that proved how even in “better” areas of the city the schools were far from good, I attended private Catholic schools: Holy Trinity for grammar school, Immaculata Prep for high school.

From there I went on to Fordham, a private, Jesuit-affiliated university in New York. My college was located in the Bronx in an area called Rose Hill. Rose Hill was something of an oasis in the surrounding seedy, urban area. I certainly learned as much outside the gates as I did within.

Probably the single most valuable thing I learned in my undergraduate work was to love learning for its own sake. I had always been a voracious reader — find me a writer who isn’t — but I tended to dread school. High school began the change, but it wasn’t until Fordham that I found myself anticipating classes. I only took one writing class and that, while pleasant, mostly taught me to finish what I began. I also learned that I could hold a reader — even a reader who, like most of those in my class, wasn’t interested in SF or Fantasy.

I graduated on the Dean’s List with a B.A. in English, and immediately went back to Fordham to pursue an M.A. and Ph.D. My undergraduate grades won me a Henry Luce Foundation Fellowship for my first two years in grad school. My last two years I held Presidential Scholarships — which was a fancy way of saying that I taught a two course load (regular professors only taught three) while attending school full-time.

By this time I was out on my own. My parents had divorced, and I was aware that there was no spare money to pay my tuition. Fordham had a policy of offering no more than four years of scholarship, so I worked my way steadily through the Masters and Ph.D. programs, finishing all but the defense of my dissertation in the allotted time. It was probably a good thing that no one told me this was impossible. I naively figured that if the University gave four years of scholarship then they expected you to finish your degree work in that time.

On my twenty-sixth birthday, I defended my dissertation (titled The Persephone Myth in D.H. Lawrence), blinked a few times, and set out to see what the world had to offer a woman with a couple published articles, a Ph.D. in English (with concentrations in Medieval, Renaissance, and Modern British Literature), and a slight knowledge of computers.

Untidy Stuff

It was the last that really got me my first full-time job. I spent the rest of that year as an adjunct professor at Fordham, giving independent tutoring, and even teaching a GRE preparation course. Then I was hired as an Assistant Professor of English at Lynchburg College in Virginia.

LC was a small college with great enthusiasm for incorporating personal computers into the students’ lives. It’s hard to imagine now how revolutionary that concept was in 1989. At Fordham, myself and another grad student had ended up with cutting edge PC’s (IBM 286’s, as I recall) because none of the full-time faculty wanted them.

I liked LC quite a bit. The faculty was friendly, devoted to teaching, and didn’t care if what I wanted to write and publish on the side was Science Fiction and Fantasy rather than academic papers. It was while I was teaching there that I wrote and sold my first short stories and novels — though none of the novels would see publication until shortly after I left. I also published a few academic papers and a biography of Roger Zelazny for Twayne’s American Author’s series.

Real lives are hard to write about in sequence because so many things happen simultaneously or overlapping. The patterns aren’t clear because you’re in the middle of them. Right after college, I married my college boyfriend. That relationship and graduate school were the frame pieces of my twenties. By the early nineties, right about the time I was starting my job at LC, the difficulties that had been slowly growing since he and I left college developed into complete alienation.

I’m not going to offer details. A wise man once said that no-one ever hears the same story from both sides of a divorce. Suffice to say that for a while the relationship was good and helped me grow into who I am. Then it was very bad indeed — and that influenced who I am, too.

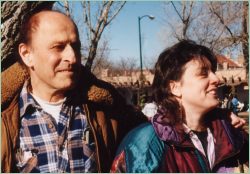

I left both the marriage and Virginia in the middle of 1994. I moved to New Mexico and took up residence with a man who had become my closest friend. I knew when I went that he had cancer, but with him was where I wanted to be.

This man was Roger Zelazny. Roger and I had started our acquaintance as pen-pals. We met for the first time at a Lunacon in Tarrytown, New York, and had the startling experience of realizing that we’d just met someone who was going to be very important in our lives. We kept corresponding — I have a file drawer packed with his letters — and the rest followed in time. I wrote the above mentioned biography of him, a fascinating project which kept bringing us together. Neither of us realized what we were getting into or that in a very few years I would be sitting on the edge of his hospital bed, sobbing my heart raw as he died.

This man was Roger Zelazny. Roger and I had started our acquaintance as pen-pals. We met for the first time at a Lunacon in Tarrytown, New York, and had the startling experience of realizing that we’d just met someone who was going to be very important in our lives. We kept corresponding — I have a file drawer packed with his letters — and the rest followed in time. I wrote the above mentioned biography of him, a fascinating project which kept bringing us together. Neither of us realized what we were getting into or that in a very few years I would be sitting on the edge of his hospital bed, sobbing my heart raw as he died.

I can’t neatly sum up the impact Roger had on my writing. He was impassioned about both the art and the craft. We talked about writing continuously. He gave me books, comics, advice, and support. He told me what I now tell aspiring writers — that persistence is the single greatest asset a writer can have. Best of all, even when it might have helped me to publish faster or more frequently, Roger never tried to turn me into a clone of himself.

After Roger died, he still had one enormous lesson to teach me. Shortly before his death, he had asked me to complete his two unfinished novels: Donnerjack and Lord Demon. Roger never outlined, but we had talked about both novels. He had read me his favorite passages, laughed at his own jokes, given me some sense of what he hoped to achieve in each — though no idea of how he meant to achieve it.

More than anything else, I wanted those last two books to be worthy of Roger. I had already read just about everything he had published when I wrote the biography. Now I remembered something he had said about how he went about writing his part of Deus Irae, a novel he wrote with Philip K. Dick. He hadn’t tried to write like Dick; instead he had studied Dick’s prose until he could manage what he called a “meta” style, blending his own and Dick’s.

I followed Roger’s lead, studied his tricks, remembered his story values — which were sometimes quite different from mine. I’m too close to both projects to say if I succeeded, but readers and reviewers seem to like the novels. What I can assuredly say is that the entire thing was a tremendous learning experience. Changer, written after I wrote Donnerjack, is a markedly different book in terms of style and use of point of view than it would have been if I had completed it before doing Donnerjack.

Now

I stayed in New Mexico after Roger died, though I moved from Santa Fe to Albuquerque. I like New Mexico. It has some of the cosmopolitan, multi-cultural feel of D.C. and New York, but is much smaller. The smallness is part of what I like. There are miles of open space where I can go hiking within a few minutes from my urban residence, but there are museums and galleries within a twenty minute drive.

I’d loved Roger with all my heart, but I was not yet thirty-three when he died. I’ve found I enjoy sharing my life with someone. Don’t get me wrong. I’d a thousand times rather be alone than live with someone incompatible or unpleasant, but given my druthers, I like to have someone with whom I can share the new rosebuds and other ordinary adventures of life.

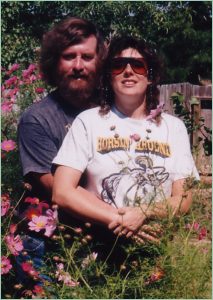

I was lucky. Someone came around when I wasn’t even thinking about a relationship, much less about falling in love and getting married again. His name is Jim Moore. He’s an extremely talented archeologist who loves SF and Fantasy, and has done some fiction writing himself. If you want to see a portrait of Jim (other than the photo on this page), try my short story “Jeff’s Best Joke” in the anthology Past Imperfect.

I was lucky. Someone came around when I wasn’t even thinking about a relationship, much less about falling in love and getting married again. His name is Jim Moore. He’s an extremely talented archeologist who loves SF and Fantasy, and has done some fiction writing himself. If you want to see a portrait of Jim (other than the photo on this page), try my short story “Jeff’s Best Joke” in the anthology Past Imperfect.

Jim and I have been married several years now, and it’s too soon to estimate his impact on my writing. I can say that having someone around who listens to me brainstorm, reads my rough drafts, helps me research, draws my maps, and contributes in a hundred thousand intangible ways to my enthusiasm and peace of mind must have a very solid and positive impact indeed.

But that part of the story is open, as is all the rest to come.

A Bit More About Jim and Me

I’ve been promising for years to update this Bio. Finally, for Jim and my 20th Wedding Anniversary, I wrote the following. It seems to fit the bill… Eventually, I’ll add a picture, but when you read below, you’ll see why that’s more difficult than it may seem!

Jim and I have known each other since sometime probably in early autumn of 1994, having met a few months after I moved to New Mexico to live with Roger Zelazny. After Roger and I settled in, I told him that the only part of my past life I really missed was gaming.

Roger said, “I think George has a group. I’ll see if he knows of anyone who is looking for players.” Apparently, George spoke with his group because, when I attended my first Bubonicon, Melinda Snodgrass came flowing up (she was all dressed up, having come directly from having lunch out with her then-in-laws) and said, “I’m Melinda. George says you’re looking for a gaming group. Would you like to join ours?”

The group Roger and I joined was mostly writers – George R.R. Martin, Melinda Snodgrass, and Walter Jon Williams were all in that initial game. But there were non-writers as well: Chip Wideman, Carl Keim, and… Jim Moore.

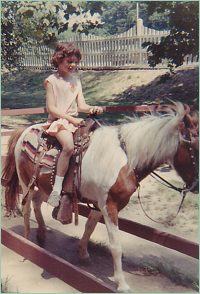

Except that for a long time, to me, Jim was just “Jim.” I don’t think I learned his surname until a year later. He was just the good-looking archeologist with the quirky sense of humor who held his own very well with the quick-witted and verbally agile writers. I gathered that, like most of the others, he was in his forties. (Carl Keim and I, both in our early thirties, were the babies of the group.)

If you want to see what Jim looked like then, there’s the snapshot above. It was taken by my dad, a year or so into our marriage, during a summer when the cosmos we’d planted did the best they ever have…

As a writer, I’m very lucky to have Jim as a partner. Many writers’ families – even their immediate families—are not interested at all in what they do. Many are not even interested in SF and F. If they attend conventions or book events, they’re often out of their depth or just along for the free vacation.

Jim, however, was a long-time SF/F reader even before I met him. He’d attended conventions and, since so many of his friends were professional writers, he already knew a great deal about what a writer did and does. In the twenty years we’ve been married, he’s built on that foundation, so that he has knowledge as extensive as any member of the profession.

Unlike many author spouses – even those who are interested in SF/F – at book events Jim’s always available to help out. At a book fair, he’ll stand for hours at my side, flapping books (that is, opening them to the correct page to be signed). He listens with endless patience to me giving variations of the same reading or talk, then dissects the event with me after.

While I’m signing or chatting with readers, Jim stays near enough to help, but also chats with people. We’ve noticed that people too shy to “take up Jane’s time” will often bring their questions to Jim. Since he’s always up-to-date on what I’m doing, he’s good person to talk to… And he’s interesting in his own right, being as passionate about archeology as I am about writing.

People often ask me – especially since archeology crops up from time to time in my writing – whether the fact that Jim is an archeologist is an influence on my choice of topic. The answer is “no” and “yes.” I was interested in archeology long before I met Jim. I wrote the first version of The Buried Pyramid before we got together. However, Jim has definitely contributed his knowledge to subsequent works.

My short story “Out of Hot Water” (from the anthology Earth, Air, Fire, Water edited by Margaret Weis) had its genesis in a visits to Ojo Caliente, where Jim was directing a dig. When I was writing “Like the Rain,” for the anthology Golden Reflections (edited by Joan Spicci Saberhagen and Robert E. Vardeman), Jim’s extensive research library came to my assistance numerous times. And he agreed to be a character in my short story “Jeff’s Best Joke” (originally in Past Imperfect, edited by Martin H. Greenberg and Larry Segriff; reprinted in my collection Curiosities). There are other examples, less direct, but in definitely places where Jim’s input mattered.

Jim has a role even in those stories that aren’t obviously archeological. He helped me narrow options when I was asked to come up with a series concept, and therefore is definitely the godfather of Firekeeper and all her friends. He is extremely patient with my tendency to become obsessive about whatever it is I’m researching at a given time. Even better, he’ll get involved with my research, going on trips, taking photos, suggesting possible areas I might want to further delve into.

When a work is done, Jim will put aside whatever he’s reading, pull out his pencil, and go through the manuscript. He’s learned I really mean it when I say I don’t want praise, I want an honest opinion. In turn, I promise that even if I don’t agree with a given comment, I’ll make a note of what he has said. If someone else says the same thing, I’ll admit that obviously I’m not communicating what I thought I was communicating and that revision is necessary.

Jim even has the tenacity to take the occasional photo of camera-shy me, which is far more of an ordeal than you may realize, especially if the photo isn’t a candid one. And, for many years now, he’s made time to take photos for the Wednesday Wanderings, Thursday Tangents, and Friday Fragments.

So, Jim’s definitely an influence on many levels, almost certainly in ways of which I am unaware, because sometimes the author is the last to figure these things out. Best of all, twenty years in, I can definitely say I’m hoping for at least twenty more. That’s got to be good, right?

All photos on this page are Copyright © by the photographers. All rights reserved.